Friends,

Please vote for my newly posted short story “Sushi to Go” on my newly created Reddit account. If you would like to give me the “I’m too lazy to read the FAQ” version of how to use Reddit, I’d sincerely appreciate it.

Pax Tibi, James

“Sushi to Go,” by James H. Peterson III

For Aziraphale and Crowley

1.

It began, or part of it began, near a motel in Salt Lake City. Several people had a very bad day. It was the sort of bad day you often dream about after you have seen a vivid and violent movie coupled with Cajun food. This bad day differed for most of the participants because they never awoke from the dream. Sensational movies, serious documentaries, and both good and bad books were written about this bad day.

Two young men were arrested and charged with crimes they did not commit. One of the young men never said anything, not even to his lawyer. The other young man confessed to everything the police told him he did. The police had told him what he did so many times and showed him so many pictures that he had come to believe, convinced by his nightmares, that he had, in fact, done the crimes. He dreamt of the slaughtered cheerleaders, the blood stained money. He dreamt of the motel manager in his sloth and the crisp clean mini-market across the dusty street, and the once pretty, now dead cashier. Most of all, he dreamt of the little girl, that one that had come to the motel with her uncle. Once the dreams started to produce prolonged insomnia, the confessing young man went onto confess to every sin he could remember. That same young man’s lawyer later tried to use the fact that the confessing young man also confessed to being James Earl Files’ back-up shooter to make the point that this client was no longer dealing with reality in any coherent fashion. The judge disallowed this evidence, and the confessing young man and his friend, were subsequently given due process, and multiple life sentences. No one on the jury was bothered by the fact that none of the physical evidence placed the young man at any of the murder scenes. He had confessed, and that was the main fact presented at his trial. Later on, almost no one would remember that the young man’s lawyer had been out of law school for less than one year, and had never argued a capital case before.

Somewhere fifteen hundred miles east, Mary Smith put down the Courier-Journal newspaper in disgust. She and her husband John had become involved with The Innocence Project after John had picked up a copy of “The Innocent Man,” by John Grisham that one of John’ students had left in his classroom. Neither of them realized at first that the novel was a non-fiction account of Ron Williamson’s life. Williamson spent 11 years on death row, more than once coming close to the last terminal show, before being cleared by DNA evidence.

Mary had been motivated to enter law school and had finished with the distinctions that only come from ignoring everything else in your life save the winning of distinctions. John had remained a history professor and continued with surgical precision pointing out death tolls, casualty counts, the logic of blood debts, the cyclical nature of violence, and the long-term consequences of this or that war to whichever of his students managed to stagger into his seminars.

Mary stood, smoothed her red, orange, and yellow sundress before walking through their apartment to the bathroom. She inhaled the cold crisp winter morning air breezing through one open kitchen window of the fourth floor Cherokee Road apartment. She remembered how that same breeze would carry the smell of coffee and Indian food from the streets below. Stopping just before the open bathroom door, she cast a critical eye over her husband.

“We are going to be late,” she said.

John finished the stroke of his razor before turning to her. One-half of his face was covered in shaving cream.

“Right, let’s go,” he said.

Mary rolled her eyes.

“Just my luck,” John said turning back to the mirror and eyeing his work. “I find the one woman in the whole city that takes less time to get ready than me, and I have to go and marry her.”

Mary foldered her arms and continued looking at her husband.

“A sundress in winter?” John asked.

Mary smiled as she stepped backward and flashed him her woolen underware.

2.

It began, or part of it began, a little less than two miles west of Mary Smith in her sunset colored sundress. In a shotgun house on Samuel Street, Jobab Jabes Miller, loaded rounds into the magazine for his Tariq 7.65mm pistol. Jo did not think while he did this. Jo had not thought much since his family had gone away.

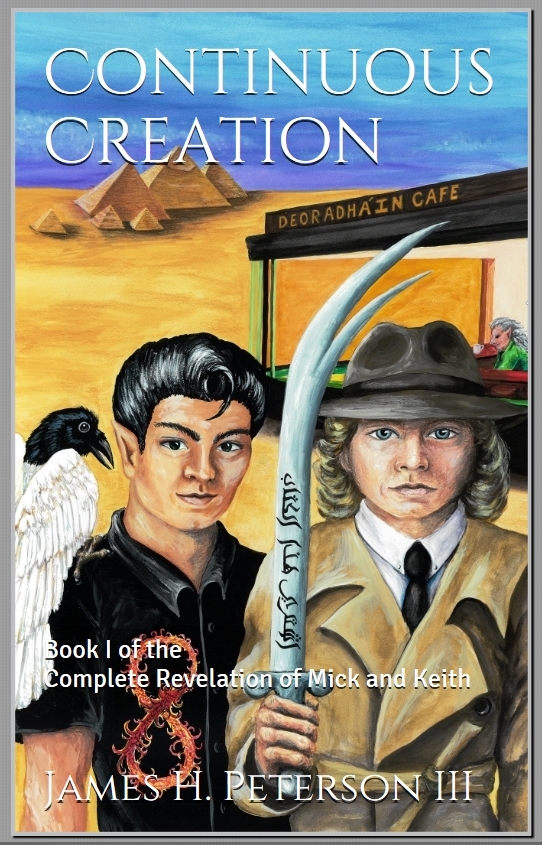

Read More of “Sushi to Go,” by James H. Peterson III